To understand Scotland, one must understand the Gaelic tradition — the ancient and enduring heart of Scottish culture. Gaelic is not just a language; it is a way of seeing the world, a worldview steeped in poetry, music, and memory. From the misty hills of the Highlands to the rocky coasts of the Hebrides, the sound of Gaelic echoes through the centuries. It is the language of the old stories, the ceilidh songs, and the haunting melodies of the bagpipes — a connection to the past that binds modern Scots to their ancestors. “It is a bond with the land itself,” wrote Sir Walter Scott, “as natural and ancient as the heather on the hills.”

Origins and Early History

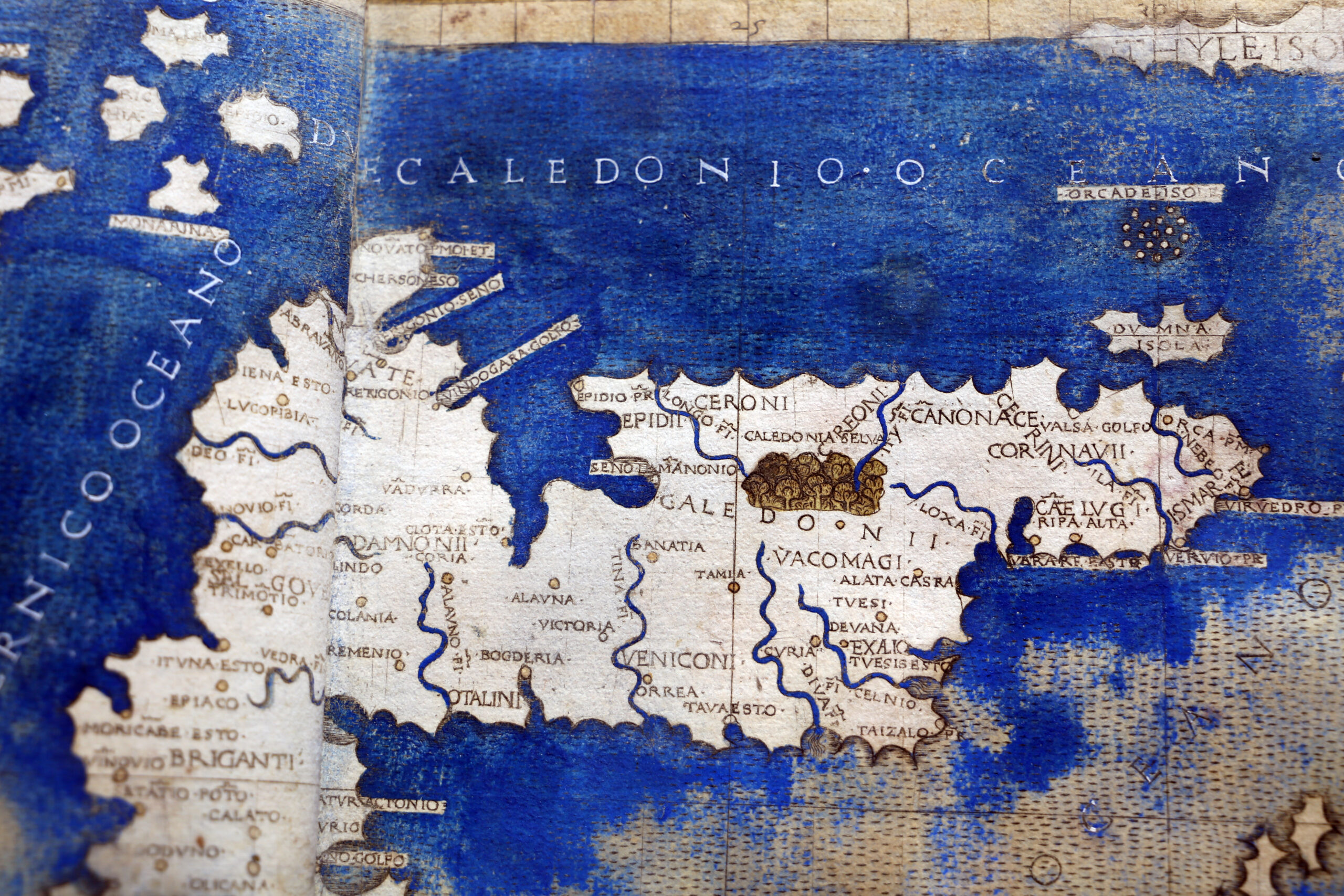

Gaelic arrived in Scotland with the Scots from Ireland around the 4th century AD. The Gaels established the kingdom of Dal Riata, centred around Argyll, where the Irish and Scottish Gaelic tongues shared a common root. Over time, Gaelic culture expanded east and north, absorbing and blending with the traditions of the native Picts. The language of the Gaels became the dominant tongue of the early Scottish kingdom, influencing not only daily life but also the early Christian church.

The monks of Iona — among them St. Columba, who arrived from Ireland in 563 AD — were steeped in Gaelic tradition. They spread Christianity throughout the Highlands and the Western Isles, carrying with them the Gaelic language and its spiritual depth. The Book of Kells, with its intricate knotwork and vibrant symbolism, reflects both Christian and Celtic artistic influence. Gaelic names, prayers, and place names began to define the Scottish landscape — from the Isle of Skye (Eilean a’ Cheò, or “Island of Mist”) to Ben Nevis (Beinn Nibheis, “Venomous Mountain”).

Yet Gaelic was more than a language of faith; it was the language of kings and warriors. Kenneth MacAlpin, who united the Scots and Picts into the Kingdom of Alba in the 9th century, spoke Gaelic as his court language. Gaelic remained the language of the Scottish court until the reign of Malcolm III (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada) in the late 11th century, when his marriage to the English princess Margaret brought a shift toward Anglo-Norman influence. Nevertheless, Gaelic remained dominant in the Highlands and the Isles, where the clan system held sway.

The Clan System and the Lords of the Isles

The Gaelic culture of Scotland found its purest expression in the clan system — a social order based on kinship, loyalty, and land. The Gaelic word clann means “children,” and the clans functioned as extended families, ruled by a chief whose authority was both political and symbolic. Clan tartans, bagpipes, and Highland games were not merely traditions — they were outward expressions of a distinct Gaelic identity.

At the heart of this Gaelic world were the Lords of the Isles. From the 12th to the 15th centuries, the MacDonalds ruled the Western Isles as a quasi-independent kingdom, with their seat at Finlaggan on Islay. The Gaelic language flourished under their patronage, and the bards composed epic poetry in honour of the chiefs. John of Islay, the first Lord of the Isles, was described as “King of the Hebrides,” and his Gaelic court was renowned for its sophistication and wealth. “The Gaelic court was the soul of Highland culture,” wrote historian John Prebble, “where honour, poetry, and war blended into a single ideal.”

Gaelic society was oral at its core. The bards were the keepers of memory, reciting tales of clan history, love, and war in flowing Gaelic verse. The ceilidh was the gathering place where songs were sung, stories told, and dances performed — the living heart of Gaelic Scotland.

The Fall of the Clans and the Highland Clearances

The fall of the Gaelic world came with the collapse of the clan system after the Jacobite risings of the 18th century. The defeat at Culloden in 1746 marked not only the end of the Jacobite cause but also the destruction of Gaelic culture. The British government, determined to suppress any future uprisings, outlawed the wearing of tartan, the carrying of arms, and even the speaking of Gaelic. The Act of Proscription of 1747 was aimed directly at dismantling the Highland way of life.

Then came the Highland Clearances. Driven by economic pressures and changing land use, landlords evicted thousands of crofters from their ancestral lands to make way for sheep farming. Entire villages were burned and families forced to emigrate to Canada, Australia, and the United States. Gaelic-speaking communities were scattered to the winds, and with them, the language and culture faced the threat of extinction. “The Clearances were not just the loss of land,” wrote Tom Devine, “they were the breaking of the Gaelic soul.”

The Romantic Revival and the Preservation of Gaelic

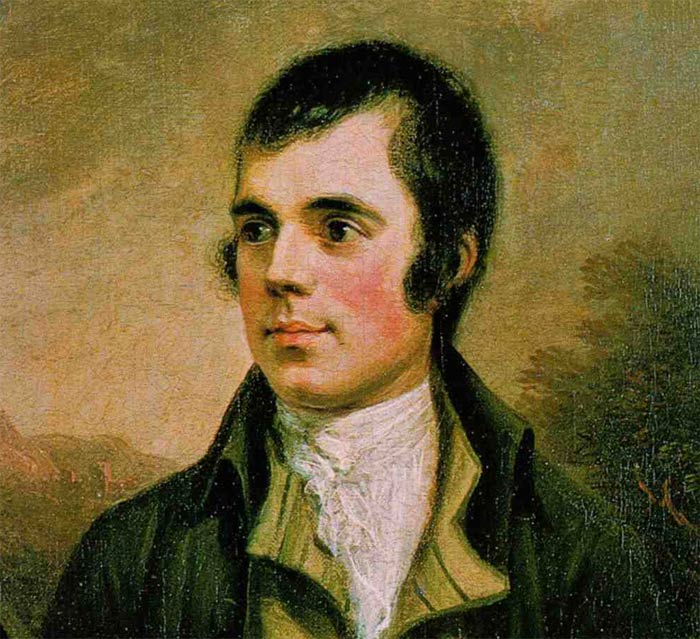

Ironically, the romantic appeal of the Highland culture, even in decline, inspired a wave of admiration and preservation. Sir Walter Scott’s novels, including Waverley (1814) and Rob Roy (1817), helped popularize Highland dress, Highland games, and the romantic image of the clansman. Scott arranged the famous “King’s Jaunt” of 1822, when King George IV visited Scotland in full Highland dress — tartan, by then a symbol of rebellion, was rebranded as a mark of royal favour.

The Gaelic language itself saw a revival through the work of poets and songwriters. James Macpherson’s Ossian cycle, published in the 1760s, claimed to be translations of ancient Gaelic poetry — though the authenticity was questioned, the impact was profound. “Ossian shaped how Europe saw Scotland,” wrote historian Murray Pittock. “It was a Scotland of myth and song, of heroes and tragedy.”

The Gaelic tradition also found strength in music. The haunting melodies of the bagpipes, the mournful beauty of the piobaireachd, and the lively reels and strathspeys became defining symbols of Scottish identity. The Gaelic Mod, established in 1891, became a festival of language, song, and poetry — a beacon for Gaelic culture in the modern age.

Gaelic Today: Resilience and Revival

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen a determined effort to preserve and revive Gaelic. The Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act of 2005 gave Gaelic official status and placed a duty on public bodies to support its use. Gaelic schools have opened in the Highlands and in Glasgow; television and radio programming in Gaelic have flourished. The National Theatre of Scotland’s 2007 production of The Cheviot, the Stag, and the Black Black Oil explored the legacy of the Clearances in Gaelic and English, bringing the story of Highland Scotland to a new generation.

Today, Gaelic is not just a language of history — it is a language of the future. “Gaelic is the voice of Scotland,” wrote historian Michael Fry. “It carries with it the memory of triumph and defeat, of love and war, of loss and survival.” The Gaelic tradition, once on the brink of extinction, now stands as a testament to the resilience of Scottish identity.

References

- Devine, T. M. The Scottish Nation: 1700–2000. Penguin Books, 1999.

- Pittock, Murray. Ossian and the Highland Myth. Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Scott, Sir Walter. Waverley. Archibald Constable and Co., 1814.

- Prebble, John. Culloden. Secker & Warburg, 1961.

- Fry, Michael. Wild Scots: Four Hundred Years of Highland History. Birlinn, 2005.