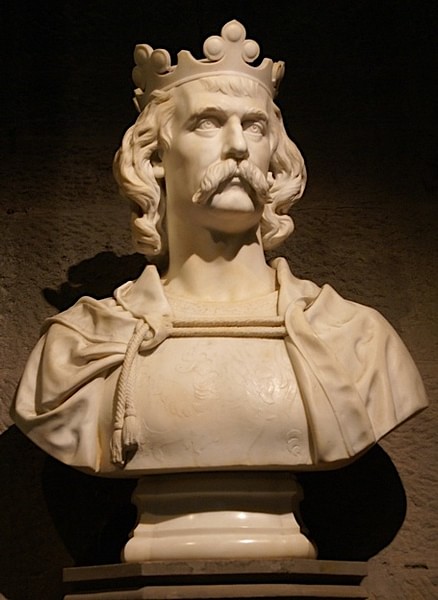

Robert I (1306–1329): The Warrior King Who Secured Scotland’s Independence

The reign of Robert I, known to history as Robert the Bruce (Roibert a Briuis), from 1306 to 1329, stands as one of the most remarkable and transformative periods in Scottish history. Rising to power during the chaotic aftermath of the First War of Scottish Independence, Robert faced the near-total collapse of Scottish sovereignty under the military dominance of Edward I of England. Through a combination of strategic brilliance, ruthless determination, and political acumen, Robert transformed a divided and weakened Scotland into a united kingdom that secured its independence from English dominance. His victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 remains one of the most celebrated moments in Scottish history—a testament to his leadership and military genius.

Robert’s reign was shaped by the brutal realities of medieval warfare and the fragile political foundations of the Scottish monarchy. After his dramatic seizure of the crown in 1306 and his early defeats, Robert faced the ruthless military might of England under Edward I and, later, Edward II. His ability to recover from early setbacks, rally the Scottish nobility, and adopt innovative guerrilla warfare tactics eventually turned the tide of the conflict. By the time of his death in 1329, Robert I had secured Scotland’s position as an independent kingdom and laid the foundation for the House of Bruce’s dominance. His reign remains a defining moment in Scottish national identity—a period when the survival of the Scottish nation hinged on the resilience and courage of one man. As historian Michael Lynch observes, “Robert the Bruce was more than a warrior king—he was the architect of Scottish independence, a figure whose legacy shaped the political and military course of Scotland for centuries to come” (Lynch, 1991).

Robert Bruce was born on 11 July 1274 at Turnberry Castle in Ayrshire. He came from one of Scotland’s most powerful aristocratic families. His grandfather, Robert de Brus, had been one of the original claimants to the Scottish throne during the Great Cause of 1291–1292—a period when Scotland’s monarchy was left vacant after the death of Alexander III and his granddaughter, Margaret, Maid of Norway. The Bruce family held extensive landholdings in both Scotland and England, giving them a complex political identity that placed them at the center of the Anglo-Scottish conflict. Robert’s father, Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale, initially supported the claim of John Balliol to the Scottish throne. However, after Balliol’s abdication and the English occupation of Scotland under Edward I, the Bruces aligned themselves with the growing movement for Scottish resistance.

By the early 1300s, Scotland was under near-total English control. Edward I had imposed direct rule through a network of castles and garrisons, and the Scottish resistance, led by figures such as William Wallace, had suffered a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298. Wallace’s capture and execution in 1305 left the Scottish resistance leaderless and divided. It was in this political vacuum that Robert Bruce emerged as a central figure. Recognizing that the path to Scottish independence lay in reclaiming the crown, Bruce made a bold and ruthless bid for power.

On 10 February 1306, Bruce murdered his political rival, John Comyn (the Red Comyn), at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries. Comyn, a member of one of Scotland’s most powerful noble families, had been a key ally of the Balliol faction and a potential claimant to the Scottish throne. The killing of Comyn fractured the fragile unity of the Scottish nobility and sparked a political and military crisis. On 25 March 1306, Bruce was crowned King of Scots at Scone, with the ceremonial blessing of Bishop William Lamberton. However, his ascension was immediately contested by the pro-English faction within Scotland and by Edward I of England, who viewed Bruce’s claim as an act of rebellion.

Edward I’s response was swift and brutal. English forces, led by Aymer de Valence, defeated Bruce’s army at the Battle of Methven in June 1306. Bruce was forced into hiding, and his supporters—including his wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, and his daughter, Marjorie—were captured and imprisoned. Bruce spent the winter of 1306–1307 in hiding, reportedly living in a cave on Rathlin Island off the coast of Northern Ireland. According to legend, it was during this period of exile that Bruce, inspired by the perseverance of a spider trying to weave its web, resolved to continue his fight for the Scottish crown. Michael Lynch argues that “Bruce’s survival during this period was nothing short of miraculous—his political and military base had collapsed, yet his determination to reclaim the throne remained unshaken” (Lynch, 1991).

The death of Edward I in July 1307 provided Bruce with an opportunity to regroup and reorganize. His military strategy shifted from open-field battles to guerrilla warfare—a tactic that played to the strengths of the Scottish terrain and the mobility of his forces. Between 1307 and 1314, Bruce led a series of daring and strategically brilliant raids against English-held castles and outposts. He recaptured castles in Galloway, Argyll, and Ayrshire. In 1310, Bruce conducted raids deep into northern England, undermining Edward II’s authority. By 1313, Bruce had secured the surrender of Perth, Dundee, and Edinburgh, dismantling the English military infrastructure in Scotland.

Bruce’s guerrilla strategy culminated in the decisive Battle of Bannockburn on 23–24 June 1314. Facing a numerically superior English force under Edward II, Bruce used the terrain and superior tactics to devastating effect. The Scottish schiltrons—tight formations of spearmen—repelled repeated English cavalry charges, and the English army was routed. Richard Oram states that “Bannockburn was not just a military victory—it was a political and psychological triumph that secured Bruce’s legitimacy and Scotland’s independence” (Oram, 2011).

Following Bannockburn, Bruce focused on securing international recognition of Scotland’s independence. In 1320, the Scottish nobility issued the Declaration of Arbroath—a powerful assertion of Scottish independence addressed to Pope John XXII. The Declaration affirmed that the Scottish crown was not subject to English overlordship and that Robert I ruled by the consent of the Scottish people. Pope John XXII’s eventual recognition of Bruce’s kingship in 1324 strengthened Scotland’s diplomatic position. In 1328, Bruce secured the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, in which Edward III formally recognized Scotland’s independence and Robert I as king.

Robert I’s reign was not without setbacks. His early defeats at Methven and Kildrummy nearly ended his reign. The internal rivalries among Scottish nobles remained a threat to Bruce’s authority, and his health declined in his later years due to leprosy. Despite these challenges, Bruce’s accomplishments were monumental. His victory at Bannockburn secured Scotland’s military independence, the Declaration of Arbroath established Scotland’s sovereign legitimacy, and Bruce’s military campaigns restored the authority of the Scottish crown.

Robert I died on 7 June 1329 at Cardross. His body was buried at Dunfermline Abbey, but his heart was removed and taken to the Holy Land as part of a pilgrimage led by Sir James Douglas—a final gesture of Bruce’s lifelong commitment to the cause of Christian kingship and Scottish independence. His reign transformed Scotland from a kingdom on the verge of collapse into a politically independent and militarily secure state. As Michael Lynch concludes, “Robert the Bruce was Scotland’s greatest king—not only a warrior and a leader, but the savior of the Scottish crown” (Lynch, 1991).

References

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. Edinburgh University Press.

- Lynch, Michael. (1991). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Tempus Publishing.