Macbeth (1040–1057): The Real King Behind the Legend

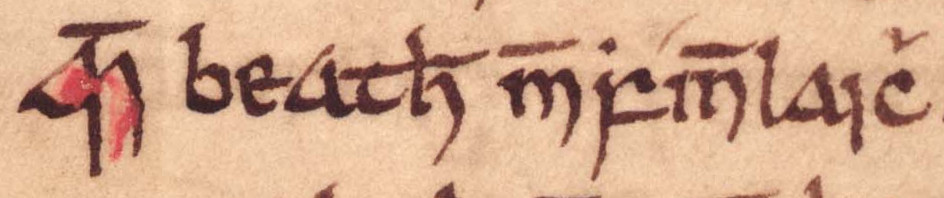

The reign of Macbeth (Mac Bethad mac Findláich), from 1040 to 1057, has been overshadowed by the dark and distorted legacy created by William Shakespeare’s famous tragedy. In reality, Macbeth was not the ruthless and bloodthirsty tyrant portrayed in literature but a capable and pragmatic ruler who brought a period of stability to the Scottish throne after years of dynastic conflict. His rise to power through the defeat of Duncan I (Donnchad mac Crínáin) in 1040 was not an act of treachery, but part of the ongoing Gaelic system of tanistry—a legitimate contest for kingship among royal kin. Macbeth’s reign was characterized by internal consolidation, military defense against Viking incursions, and attempts to strengthen Scotland’s position within the broader political landscape of the British Isles and Scandinavia.

Despite his political and military successes, Macbeth’s reign ultimately ended in tragedy. His defeat at the hands of Malcolm Canmore (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada), Duncan I’s son, at the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057 brought his rule to a violent conclusion. However, Macbeth’s legacy as a ruler who preserved the integrity of the Scottish kingdom and stabilized the monarchy remains significant. As historian Michael Lynch notes, “Macbeth was not a villain but a king who ruled effectively within the context of his time—a monarch whose reign reflected the difficult balance between Gaelic traditions and the emerging realities of medieval statecraft” (Lynch, 1991).

The Rise of Macbeth and the Political Context of His Reign

Macbeth was born around 1005 into the powerful Gaelic aristocracy of northern Scotland. He was the son of Findláech mac Ruaidrí, the Mormaer of Moray—a title that gave him control over the politically significant region of Moray. The mormaers (earls) of Moray had long been rivals to the Scottish crown, maintaining a degree of political autonomy even after the consolidation of the Scottish kingdom under the House of Alpin.

Macbeth was connected to the royal line through his mother, who was a granddaughter of Malcolm II (Máel Coluim mac Cináeda). This gave Macbeth a legitimate claim to the Scottish throne under the Gaelic system of tanistry, in which the most capable male relative within the royal kin group could claim the throne through strength of arms and political support.

Macbeth’s path to kingship was shaped by the political fragmentation and dynastic conflict that followed the death of Malcolm II in 1034. Malcolm’s successor, Duncan I, was the first Scottish king to inherit the throne through primogeniture rather than tanistry. However, Duncan’s rule was marked by military failure and political weakness. His defeat in 1038 at the hands of the Northumbrians during his ill-fated siege of Durham damaged his political standing, and his failed campaigns against the Norse earldom of Orkney exposed the weakness of the Scottish crown.

In 1040, Macbeth challenged Duncan’s rule. The two armies met at Pitgaveny near Elgin. Macbeth’s forces, drawn from the seasoned warriors of Moray and Ross, decisively defeated Duncan’s army. Duncan was killed in battle—an act that was politically acceptable under the system of tanistry. Macbeth’s victory made him the undisputed king of Alba.

Alex Woolf writes that “Macbeth’s accession was not an act of regicide, but a legitimate outcome of the Gaelic system of kingship—a transition based on political consensus and military strength” (Woolf, 2007).

Political and Military Challenges

1. Internal Political Consolidation

Macbeth’s immediate challenge upon securing the throne was to consolidate his authority over the Gaelic and Pictish aristocracy. While his victory over Duncan had secured his position militarily, the political allegiance of the mormaers of Atholl, Fife, and Strathclyde remained uncertain.

Macbeth’s political strategy involved reinforcing his ties to the Gaelic aristocracy while expanding the influence of the Scottish crown. He married Gruoch, the granddaughter of Kenneth III (Cináed mac Duib), which strengthened his claim to the throne through the line of Dub and established a broader base of support among the nobility.

To secure the loyalty of the mormaers, Macbeth distributed land and military titles to key regional leaders. He also strengthened the political influence of the Scottish church by reinforcing the role of Dunkeld and St. Andrews as centers of religious authority.

Richard Oram notes that “Macbeth’s ability to hold the Scottish nobility together reflected his political acumen—he governed not through fear but through the careful distribution of power and patronage” (Oram, 2011).

2. The Viking Threat and the Defense of the Kingdom

The Norse presence in Scotland remained a significant military threat during Macbeth’s reign. The earldom of Orkney, now ruled by Thorfinn Sigurdsson (Thorfinn the Mighty), maintained control over the Northern Isles and frequently launched raids into the Scottish mainland.

Macbeth adopted a defensive military strategy toward the Norse. In 1045, his forces repelled a large Viking raid in Caithness, securing the northern frontier. He also reinforced the coastal defenses along the western seaboard and strengthened alliances with local Gaelic chieftains to resist further incursions.

Macbeth’s ability to contain the Norse threat without engaging in large-scale military conflict reflected his strategic understanding of Scotland’s military limitations.

Alex Woolf argues that “Macbeth’s defensive posture toward the Norse reflected a pragmatic approach to military strategy—he sought to defend the kingdom’s territorial integrity without overextending its military resources” (Woolf, 2007).

3. Relations with the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom

Macbeth’s foreign policy toward the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England was equally strategic. In 1050, Macbeth made a pilgrimage to Rome—a rare act for a Scottish king. His pilgrimage was widely interpreted as a diplomatic gesture aimed at securing recognition from the Papacy and strengthening Scotland’s position within the broader Christian world.

Macbeth also sought to avoid direct conflict with the Anglo-Saxon crown, which was then ruled by Edward the Confessor. He maintained a policy of diplomatic neutrality, ensuring that Scotland remained outside the expanding influence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

Michael Lynch writes that “Macbeth’s pilgrimage to Rome was not an act of piety alone—it was a calculated move to reinforce his political legitimacy and align Scotland with the growing influence of the Catholic Church” (Lynch, 1991).

Setbacks and the Fall of Macbeth

Macbeth’s reign was ultimately undone by the dynastic ambitions of Duncan’s son, Malcolm Canmore (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada). Malcolm had sought refuge in England after his father’s death, where he secured the backing of Edward the Confessor.

In 1054, Malcolm invaded Scotland with an army supported by the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. Macbeth’s forces confronted Malcolm’s army at the Battle of Dunsinane. Macbeth was defeated but escaped the battlefield, retreating to Moray.

In 1057, Malcolm’s forces pursued Macbeth to Lumphanan, where Macbeth was killed in battle.

Accomplishments and Legacy

1. Military Stability

Macbeth’s successful defense of Scotland’s northern and western frontiers secured the kingdom’s territorial integrity.

2. Political Legitimacy

Macbeth’s ability to govern for 17 years reflected the growing stability of the Scottish monarchy.

3. Cultural and Religious Influence

Macbeth’s pilgrimage to Rome reinforced Scotland’s position within the Catholic world and elevated the moral authority of the Scottish crown.

References

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981). Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press.

- Lynch, Michael. (1991). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico.

- Woolf, Alex. (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Tempus Publishing.