James II (1437–1460): The Fiery King and the Centralization of Power

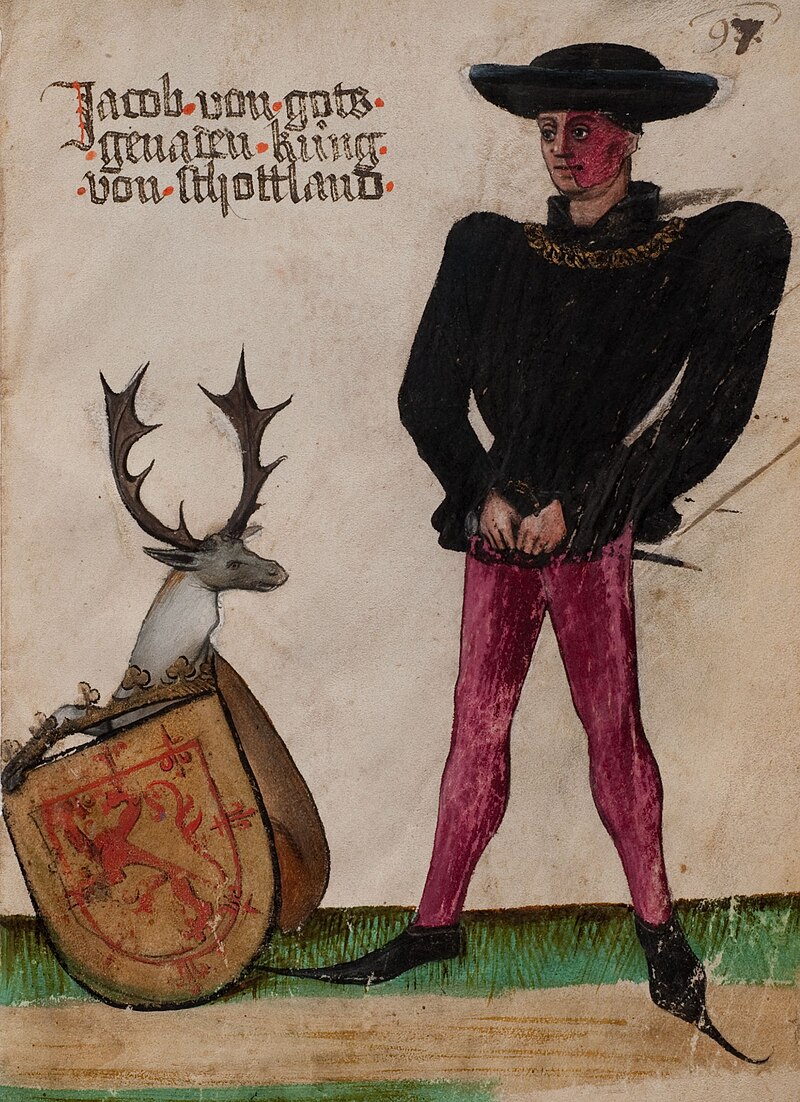

The reign of James II (Seumas II Stiùbhart), from 1437 to 1460, was a period of political consolidation and ruthless determination to secure royal authority in Scotland. Known as the “Fiery Face” due to a distinctive birthmark on his cheek, James II came to the throne as a child after the violent assassination of his father, James I. His early reign was marked by the regency of powerful nobles, fierce rivalries among the aristocracy, and the growing influence of the Douglas family. However, as James matured, he emerged as a forceful and politically astute king, determined to reassert the authority of the crown and break the power of Scotland’s over-mighty nobles.

James II’s reign reflected a shift from the fragile, decentralized nature of medieval Scottish monarchy toward a more centralized and militarily capable state. His aggressive approach to noble resistance—particularly his brutal suppression of the House of Douglas—transformed the political landscape of Scotland. James’s ambitious program of castle-building and his successful campaigns against English-held territories in southern Scotland further strengthened the crown’s authority. Yet his reign ended in sudden and dramatic fashion: killed by an exploding cannon while besieging Roxburgh Castle in 1460. As historian Michael Brown observes, “James II was a king who ruled with fire and steel—a monarch whose determination to crush aristocratic defiance laid the foundation for a stronger, more centralized Scottish state” (Brown, 2004).

The Rise of James II and the Political Context of His Reign

James II was born on 16 October 1430 at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, the youngest surviving son of James I and Joan Beaufort. His birth came during a period of significant political tension in Scotland. His father, James I, had returned from captivity in England in 1424 and initiated a bold campaign of political and judicial reform. Determined to strengthen royal authority, James I suppressed the Albany Stewarts and sought to curtail the influence of Scotland’s powerful aristocracy. However, this aggressive approach alienated the nobility and left James I politically isolated.

On the night of 20 February 1437, James I was assassinated at Blackfriars Monastery in Perth by a faction of nobles led by Robert Graham and Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl. The murder left the six-year-old James II as king, but the political reality was far more complex. Scotland’s government fell into the hands of rival factions of the nobility, each seeking to dominate the crown and use James II’s minority to advance their own interests.

The regency was initially controlled by Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Douglas and Sir Alexander Livingston of Callendar. However, power shifted dramatically in 1439 when Livingston staged a coup, capturing James II’s mother, Queen Joan, and seizing control of the young king. Over the next several years, a complex rivalry emerged between Livingston and the Douglases, with James II caught between the two factions.

Michael Lynch argues that “James II’s minority reflected the broader structural weakness of the Scottish crown—without a strong adult monarch, the nobility operated with near-impunity, using the royal court as a platform for personal advancement” (Lynch, 1991).

Political and Military Challenges

1. The Rise and Fall of the Douglases

The greatest challenge to James II’s authority came from the House of Douglas—a powerful aristocratic family that had established itself as the dominant political and military force in Scotland during the early 15th century. The Douglases controlled vast landholdings in southern Scotland and commanded the allegiance of a private army capable of rivaling the crown’s forces.

When William Douglas, 8th Earl of Douglas, succeeded to the earldom in 1443, he immediately asserted his independence from royal authority. Douglas allied himself with the Lord of the Isles and the Earl of Crawford, creating a powerful faction that openly challenged James II’s government. In response, James II adopted a strategy of divide and conquer, exploiting rivalries within the Douglas family and encouraging defections from their ranks.

The conflict escalated dramatically in 1452 when James II invited William Douglas to a royal meeting at Stirling Castle. During the meeting, Douglas refused to renounce his alliance with the Lord of the Isles. In a fit of rage, James II personally stabbed Douglas to death. James’s retainers followed suit, hacking Douglas’s body apart in a gruesome display of royal retribution.

James’s assassination of Douglas shocked the political establishment but sent a clear message that the crown would no longer tolerate aristocratic defiance. Over the next several years, James systematically dismantled the Douglas power base:

- In 1455, James led a military campaign against the Douglases, capturing their castles at Abercorn, Threave, and Douglas.

- The Parliament of Scotland passed an act of forfeiture against the Douglases, stripping them of their lands and titles.

- The final destruction of the Douglas faction at the Battle of Arkinholm in 1455 ended their dominance and left James II as the undisputed political authority in Scotland.

Richard Oram notes that “James II’s destruction of the Douglases marked the turning point in Scotland’s medieval history—the crown emerged from the conflict stronger than ever, with the power of the nobility decisively weakened” (Oram, 2011).

2. Military Expansion and Castle Building

James II was one of the most militarily active of Scotland’s medieval kings. Following the defeat of the Douglases, he turned his attention to reclaiming English-held territory in southern Scotland. In 1456, James launched a campaign to recover Berwick and Roxburgh—two strategically vital border castles that had been under English control since the 14th century.

James also undertook an ambitious program of castle-building and fortification. He constructed powerful artillery towers and curtain walls at Stirling, Linlithgow, and Edinburgh. James’s investment in artillery—particularly large cannons known as “bombards”—reflected his determination to modernize Scotland’s military capacity.

Michael Brown writes that “James II’s military reforms transformed the Scottish army from a feudal force into a professionalized military—his use of artillery in particular gave the Scottish crown a new strategic advantage” (Brown, 2004).

3. Conflict with England and Death at Roxburgh

James II’s campaign to recover Roxburgh Castle in 1460 was the climax of his military ambition. Roxburgh was one of the last remaining English-held fortresses on Scottish soil. James brought his full military strength to bear in a siege of the castle, deploying his artillery to batter the walls.

On 3 August 1460, James was standing near one of his cannons when it exploded, killing him instantly. His death was a shocking and sudden end to a reign that had been defined by militarism and political consolidation.

James’s nine-year-old son, James III, was immediately proclaimed king, but the political and military foundation laid by James II ensured the survival of the Stewart dynasty.

Accomplishments and Legacy

James II’s reign was one of the most transformative in Scottish history. His decisive action against the Douglases broke the power of the nobility and established the crown as the dominant political force in Scotland. His military reforms and investment in artillery strengthened Scotland’s strategic position. His aggressive territorial policy recovered key border regions and reinforced Scotland’s independence from England.

Despite his untimely death, James II left behind a more centralized and militarily capable kingdom. As Michael Lynch concludes, “James II’s reign was the birth of the modern Scottish state—a king who ruled not by consensus, but by force of arms and strength of will” (Lynch, 1991).

Conclusion

James II was a warrior king who ruled with fire and steel. His destruction of the Douglas faction and his modernization of Scotland’s military reflected his determination to assert royal authority over the nobility and secure Scotland’s independence from English domination. His death at Roxburgh was a fitting end to a reign defined by martial vigor and political ruthlessness.

References

- Lynch, Michael. (1991). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico.

- Brown, Michael. (2004). The Stewart Dynasty. Edinburgh University Press.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Tempus Publishing.