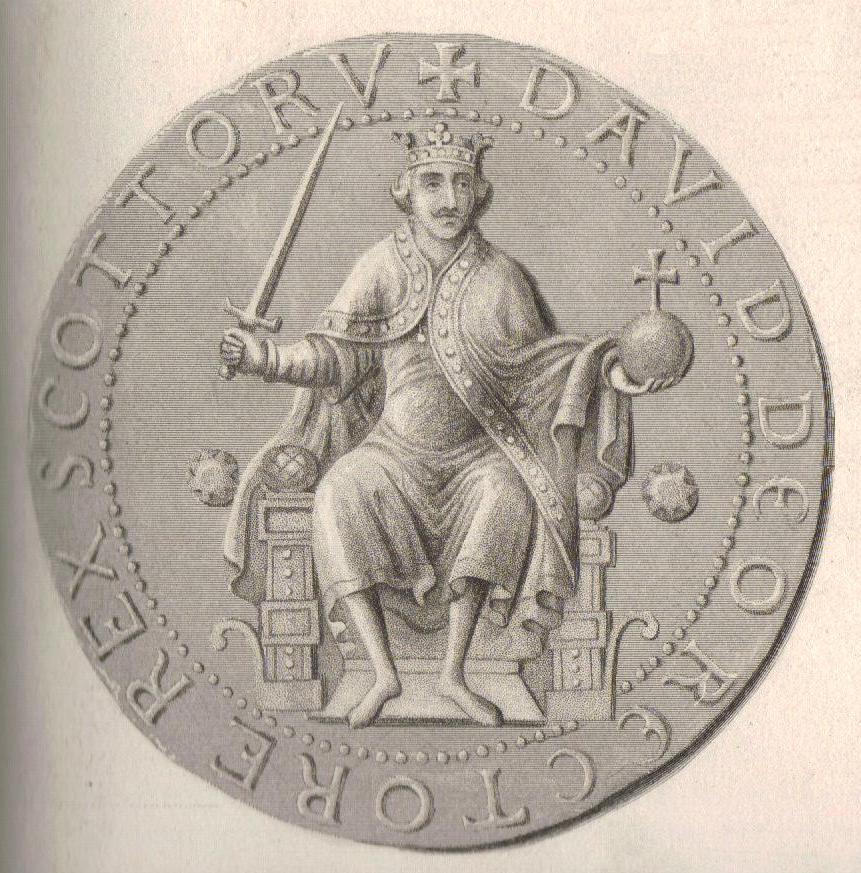

David I (1124–1153): The Architect of Feudal Scotland

The reign of David I (Dabíd mac Maíl Choluim), from 1124 to 1153, was one of the most transformative in the history of medieval Scotland. David I was not only a warrior king and political reformer but also a sophisticated statesman whose reign laid the foundations for Scotland’s emergence as a feudal kingdom aligned with the political, economic, and religious systems of medieval Europe. His rule marked the consolidation of the House of Dunkeld’s control over the Scottish crown, the introduction of feudal landholding, the rise of burghs (towns), and the establishment of a reformed church aligned with the Roman Catholic hierarchy.

David I’s reign began at a time when Scotland was still shaped by its Gaelic past—its political structures based on the system of tanistry (succession by the most capable male), its landholding patterns reflecting ancient kin-based lordship, and its church still partially influenced by the older Celtic Christian tradition. David’s long exposure to the Anglo-Norman court of Henry I of England and his close ties to the Norman aristocracy enabled him to introduce profound changes to Scottish governance. These reforms—often referred to collectively as the “Davidian Revolution”—ushered in an era of centralized royal authority and economic modernization.

David’s reign was not without challenges. His attempts to expand Scottish influence into northern England brought him into conflict with the English crown, while his elevation of Norman knights to positions of political and military power alienated segments of the Gaelic nobility. Yet despite these tensions, David succeeded in reshaping the political and economic structure of Scotland and securing the legacy of the Dunkeld dynasty. As historian Richard Oram notes, “David I was the maker of medieval Scotland—the king whose vision and policies transformed Scotland from a tribal kingdom into a feudal state” (Oram, 2011).

The Rise of David I and the Political Context of His Reign

David I was born around 1084 as the youngest son of Malcolm III (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada) and Margaret of Wessex. Through his mother, David was directly descended from the Anglo-Saxon royal house of Wessex—a lineage that linked him to Alfred the Great and the old English monarchy.

After the death of Malcolm III at the Battle of Alnwick in 1093, David’s older brother, Edgar (Édgair mac Maíl Choluim), succeeded to the Scottish throne with the backing of the Anglo-Norman crown. David was sent to the court of Henry I of England, where he was raised and educated in the Anglo-Norman tradition.

At Henry’s court, David absorbed the political and military structures of Norman England. He became familiar with the principles of feudal landholding, centralized governance, and military organization. David also established close personal ties with the Anglo-Norman aristocracy, including the powerful earls of Northumberland and Huntingdon.

In 1113, Henry I granted David the title of Earl of Huntingdon through his marriage to Matilda of Huntingdon (Maud), the daughter of Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria. This marriage gave David control over vast estates in northern England and elevated him to a position of political prominence within the Anglo-Norman aristocracy.

David’s rise to the Scottish throne was secured after the death of his brother, Alexander I, in 1124. Alexander had left no legitimate heir, and David’s claim was supported by his Anglo-Norman allies and the Scottish Church. However, his succession was not universally accepted. The Gaelic nobility of Moray and Ross supported the rival claim of Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair, Alexander I’s illegitimate son. David’s early years as king would be defined by his efforts to suppress this challenge and consolidate his authority over the kingdom.

Michael Lynch writes that “David’s accession marked the final victory of the Anglo-Norman political order over the older Gaelic kingship—his reign was the point of no return in Scotland’s transition to a feudal state” (Lynch, 1991).

Political and Military Challenges

1. The Rebellion of Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair (1125–1134)

David’s first major challenge as king came from his nephew, Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair, who led a rebellion among the Gaelic nobility of Moray and Ross in 1125.

Máel Coluim sought to restore the older system of Gaelic kingship, in which the crown was not passed by direct inheritance but by the selection of the most capable male of the royal line. He gained the support of several powerful mormaers (regional rulers) who opposed David’s introduction of feudal structures.

David responded by raising an army composed of both Gaelic warriors and Anglo-Norman knights. His military campaign against Máel Coluim was brutal and methodical. By 1130, David had crushed the rebellion and executed Máel Coluim. The territory of Moray was brought under direct royal control, and its lands were redistributed to David’s Norman allies.

Richard Oram explains that “David’s suppression of the Moray rebellion marked a decisive moment in Scottish history—it represented the triumph of the centralized monarchy over the Gaelic aristocracy” (Oram, 2011).

2. Conflict with England and the Treaty of Durham (1139)

David’s ambitions extended beyond the Scottish kingdom. His claim to the earldom of Northumberland brought him into direct conflict with the Anglo-Norman crown.

Following the death of Henry I in 1135, David supported the claim of his niece, Empress Matilda, to the English throne. This placed him in opposition to Stephen of Blois, who had seized the English crown.

David invaded Northumberland in 1138, but his forces were defeated at the Battle of the Standard near Northallerton. Despite this military setback, David negotiated favorable terms in the subsequent Treaty of Durham (1139). Under the treaty, David’s son, Henry, was granted the earldom of Northumberland. This extended Scottish influence into northern England and reinforced the power of the Scottish crown.

Michael Lynch notes that “David’s diplomatic success after the Battle of the Standard demonstrated his political acumen—despite military defeat, he secured territorial gains that enhanced the strategic position of the Scottish kingdom” (Lynch, 1991).

3. Religious Reform and the Foundation of Burghs

David’s most enduring legacy lies in his promotion of religious reform and economic modernization. He established Augustinian and Cistercian monasteries throughout Scotland, including abbeys at Melrose, Jedburgh, Holyrood, and Dunfermline.

David also introduced the concept of burghs—fortified towns established under royal charter—which became centers of trade and economic activity. These burghs were populated by merchants from Flanders, England, and Normandy, and they facilitated the growth of a market-based economy.

David’s chartering of burghs helped to integrate Scotland into the wider European economic network. The burghs became vital sources of tax revenue and reinforced the power of the crown over local economic activity.

Alex Woolf argues that “David’s creation of the burghs was a revolutionary step—he transformed Scotland from an agrarian society into a market-based economy integrated into European trade networks” (Woolf, 2007).

Setbacks and Challenges

- David’s reliance on Anglo-Norman knights alienated segments of the Gaelic nobility.

- His claim to Northumberland created ongoing friction with the English crown.

- His expansion of feudal structures contributed to social and political tension in the Highlands.

Death and Legacy

David I died on May 24, 1153 at Carlisle. He was succeeded by his grandson, Malcolm IV, who inherited a kingdom strengthened by David’s military and political reforms.

David I’s reign is remembered as the turning point in Scottish history—a period when the older Gaelic political order gave way to a centralized, feudal monarchy aligned with the political and economic structures of medieval Europe.

References

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981). Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press.

- Lynch, Michael. (1991). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico.

- Woolf, Alex. (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Tempus Publishing.