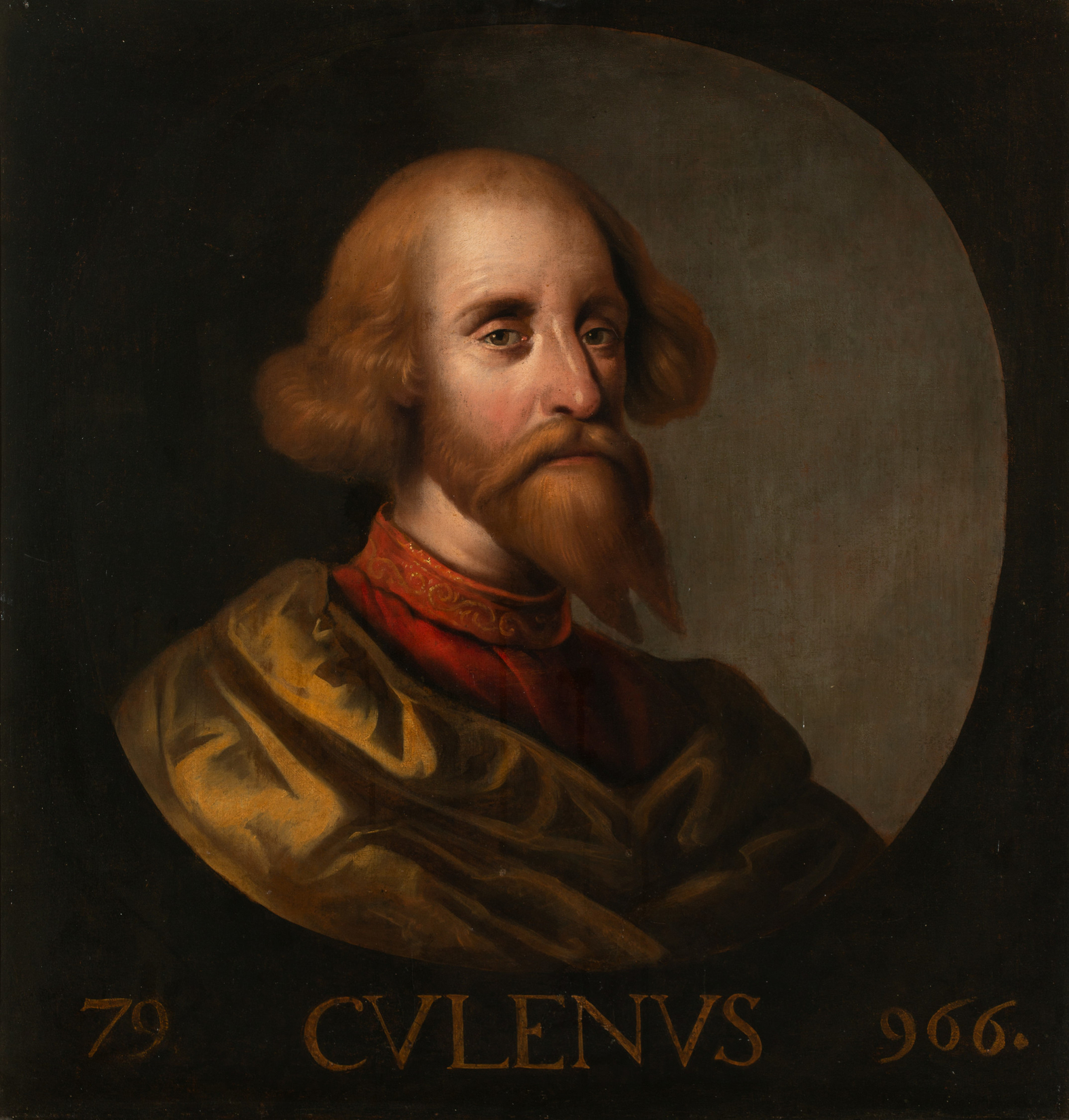

Cuilén (967–971): The Tragic Reign of the House of Alpin

The reign of Cuilén (Cuilén mac Ildulb) from 967 to 971 was brief, violent, and marked by deep political fragmentation within the kingdom of Alba. Cuilén ascended the throne after the violent death of Dub (Dub mac Maíl Coluim) at the Battle of Forres in 967—a dynastic conflict that reflected the deep divisions within the House of Alpin and the ongoing struggle between the Gaelic and Pictish aristocracies for dominance over the Scottish crown. Though his reign lasted only four years, Cuilén’s kingship was significant for the internal factionalism it exposed, the enduring Viking threat it faced, and the strategic failure to secure lasting political unity within the kingdom of Alba. His reign ended abruptly in assassination—a violent conclusion that reflected the fragile nature of medieval Scottish kingship.

Cuilén’s reign is often dismissed as a period of political instability, but it also marked an important transition in the House of Alpin’s history. The growing influence of the Gaelic nobility, the consolidation of royal authority in Lothian and Strathclyde, and the increasing tensions with the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England were all defining features of Cuilén’s short but impactful reign. As historian Michael Lynch notes, “Cuilén’s reign was the closing act of a turbulent chapter in Scottish history—a reign defined by dynastic rivalry, military weakness, and political fragmentation” (Lynch, 1991).

The Rise of Cuilén and the Political Context of His Reign

Cuilén was the son of Indulf (Idulb mac Causantín), who had ruled Scotland from 954 to 962 and had expanded Scottish territory through the annexation of Lothian. Indulf’s death in battle against Viking raiders at Invercullen left the kingdom vulnerable to dynastic conflict.

Following Indulf’s death, the throne passed to Dub, the son of Malcolm I (Máel Coluim mac Domnaill), who ruled from 962 to 967. Dub’s reign was marked by internal conflict, particularly with Cuilén’s faction, which represented the competing branch of the House of Alpin descended from Constantine II.

The dynastic rivalry between Dub and Cuilén culminated in the Battle of Forres in 967, where Dub was defeated and killed by a coalition of Moray and Atholl nobles allied with Cuilén. This victory allowed Cuilén to seize the throne.

Alex Woolf describes Cuilén’s rise as “a moment of reckoning for the House of Alpin—an attempt to impose a new political order on a kingdom still divided along dynastic and geographic lines” (Woolf, 2007).

Cuilén’s ascension was supported primarily by the Gaelic nobility of Dál Riata and the mormaers (regional governors) of Moray and Atholl, but he faced opposition from the Pictish aristocracy in the east and from the Norse settlements in the north and west. His kingship, therefore, was contested from the outset.

Political and Military Challenges

1. Dynastic Conflict and Internal Instability

The primary challenge of Cuilén’s reign was maintaining political stability within the kingdom of Alba. The House of Alpin had ruled Scotland since the mid-9th century, but the principle of tanistry—where succession was determined by the consensus of the royal family rather than primogeniture—ensured that the throne was always vulnerable to dynastic rivalry.

Cuilén’s claim to the throne was challenged by the supporters of Dub’s son, Kenneth (Cináed mac Dub), who represented the competing branch of the Alpin dynasty. While Cuilén’s victory at Forres had secured his position temporarily, Kenneth’s supporters remained active in Moray and the western highlands, where local lords resisted Cuilén’s authority.

Cuilén’s attempt to consolidate power through military campaigns in Moray and Ross was only partially successful. He suppressed a rebellion in 968, but the continued resistance of the Moray nobility weakened his ability to project authority over the northern territories.

Richard Oram notes that “Cuilén’s reign reflected the structural weakness of early Scottish kingship—his authority extended only as far as his ability to command loyalty among the regional lords, many of whom retained their own military and political ambitions” (Oram, 2011).

2. The Viking Threat

The Norse presence in Scotland remained a persistent challenge during Cuilén’s reign. The Earldom of Orkney, ruled by the descendants of the legendary Viking chieftain Rognvald, functioned as an independent Norse kingdom that frequently launched raids into Scotland.

In 970, a Norse fleet attacked the eastern coast of Scotland, targeting settlements in Caithness and Moray. Cuilén’s response was limited; he lacked the naval strength to confront the Norse directly, and his attempts to raise an army from the mormaers of Moray were met with lukewarm support.

Cuilén’s defensive strategy involved reinforcing coastal defenses and securing political alliances with the Norse rulers of Dublin. While this prevented further large-scale Viking incursions, it exposed the kingdom’s military vulnerability.

Michael Lynch argues that “Cuilén’s inability to confront the Norse threat directly reflected the fragmented nature of Scottish military power—without the full support of the regional nobility, his capacity for defense was severely limited” (Lynch, 1991).

3. Anglo-Saxon Influence and Border Conflict

Cuilén’s reign also saw growing tension with the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex under Edgar the Peaceful. The Scottish annexation of Lothian under Indulf had created a new political reality—the Scottish crown now controlled territory that had historically been part of the Anglo-Saxon sphere of influence.

In 969, Edgar summoned Cuilén to a council at Chester, where Cuilén was reportedly forced to swear fealty to the English king. While this did not result in direct Anglo-Saxon intervention, it weakened Cuilén’s standing among the Scottish nobility, who resented the implication of Scottish vassalage to Wessex.

Alex Woolf states that “Cuilén’s submission to Edgar was a political necessity, but it reinforced the perception of Scottish weakness at a time when the kingdom needed to assert greater independence” (Woolf, 2007).

Setbacks and the Fall of Cuilén

The most dramatic event of Cuilén’s reign—and the one that ultimately led to his downfall—was his death in 971. According to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, Cuilén was killed by Riderch, the king of Strathclyde, after Cuilén reportedly abducted and raped Riderch’s daughter.

The murder of Cuilén was not merely a personal act of revenge—it reflected the fragile political relationship between Alba and Strathclyde. Cuilén’s death created a power vacuum that was immediately exploited by the supporters of Kenneth mac Dub, who seized the throne in the aftermath.

Michael Lynch describes Cuilén’s death as “the ultimate failure of his kingship—an act of personal recklessness that undermined the political stability of the kingdom and handed power to his enemies” (Lynch, 1991).

Accomplishments and Legacy

1. Consolidation of Lothian

Cuilén’s reign reinforced Scotland’s hold over Lothian, securing a key strategic and economic territory for future expansion.

2. Political Instability

The internal divisions that plagued Cuilén’s reign reflected the deep structural weaknesses of early medieval Scottish kingship. His failure to command loyalty from the Moray nobility exposed the limits of royal authority.

3. The Succession Crisis

Cuilén’s death triggered a dynastic crisis that would shape the future of the House of Alpin. His rival, Kenneth II, would seize the throne and initiate a new chapter in Scottish history.

References

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981). Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press.

- Lynch, Michael. (1991). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico.

- Woolf, Alex. (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Tempus Publishing.

O